En 1955 Mercedes dominaba en todos los terrenos , mientras las Flechas de Plata acumulaban títulos en los Grandes Premios a los mandos de Juan Manuel Fangio , los Mercedes 300SLR entregaban a la marca de Stuttgart el Campeonato de Constructores en la categoría de vehículos deportivos.

Nunca una marca había dedicado y acumulado un férreo control en todas las disciplinas.

Este fue el último capítulo de una historia que comenzó en 1952 con el primer éxito del competitivo Mercedes-Benz 300 SL (serie W 194). En los años posteriores a 1955, los ingenieros de Mercedes desviaron sus conocimientos adquiridos en los circuitos a la competición de carretera.

Mercedes-Benz enjoys a sparkling finale to the 1955 racing season

-Mercedes-Benz dominates international race events

-The brand withdraws from motorsport at the end of the season

The Silver Arrows were unbeatable in 1955. Mercedes-Benz dominated both the blue-riband Grand Prix races and the exacting long-distance races, the year ending in a suitably impressive haul of titles for the motor sport department. Juan Manuel Fangio secured the Formula One World Championship, while the 300 SLR delivered the constructors’ crown for Mercedes-Benz in the sports car category. The Stuttgart-based brand also claimed the European Touring Car Championship and the Sports Car Championships of both Italy and the USA. No manufacturer had ever exerted such an iron grip on the different disciplines and classes of car racing, from Formula One to diesel sedan competition. At the end of 1955, and with the world of motor sport reeling from this overwhelming show of strength, Daimler-Benz AG pulled out of front-line motor racing. This was the final chapter in a story which started in 1952 with the first competitive success of the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL (W 194 series). In the years after 1955, the company’s development engineers diverted their expertise from the racetrack to the road.

A new beginning

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, Daimler-Benz AG had more pressing matters to attend to than achieving success on the racetrack. First on the to-do list was to reconstruct the plants destroyed in the war (Untertürkheim and Sindelfingenwere particularly badly affected) and restart volume production. Customer service and export activities also had to be reorganized. Truck production got back underway in 1945 and the first post-war passenger cars left the factories in 1946. The Mercedes-Benz 170 V, which had already been built between 1936 and 1942, got the ball rolling. In motor sport circles, meanwhile, there were rumours that the W 165 racing car might be on its way back to the track. This was the same 1.5-liter model which Hermann Lang and Rudolf Caracciola had driven to a 1-2 victory in the 1939 Grand Prix of Tripoli. However, the speculation was to remain unfulfilled. Mercedes-Benz’ former works drivers, mechanics and engineers turned their attention to vehicle repairs in that early post-war period. As the automotive historian Louis Sugahara recalled, a talent for improvisation honed over a number of years had equipped the racing team’s experts more effectively for the job in hand than their counterparts in production. It wasn’t until 1950 that the motor sport department was back in business – on the initiative of Daimler-Benz Chairman Wilhelm Haspel and under the proven leadership of Alfred Neubauer. Neubauer’s first task was to round up some functioning Grand Prix cars from the 1930s. Out of a total of four W 154 models (two of which the company purchased using a new Mercedes-Benz 170 V as bait) and six racing engines, the motor sport engineers built three operational race cars with four engines. The competitiveness of these freshly restored Silver Arrows, which had delivered Mercedes-Benz so many Grand Prix victories more than a decade earlier, was put under the microscope in two races in Argentina in 1951. Hermann Lang, Karl Kling and the local man Juan Manuel Fangio drove impressively in Buenos Aires, Lang and Kling recording second place finishes on February 18 and 24 respectively. However, the performance of the fast but heavy cars was no longer sufficient to secure race wins. Rudolf Caracciola, Mercedes-Benz’ most successful driver before the war, had suggested as much to Alfred Neubauer even before the team left for Argentina, and turned down the offer of a drive in the revived Silver Arrows. Initially, Neubauer also had his sights set on the 1951 Indianapolis 500 race, but pulled the plug on that idea on the back of the lessons learned in Argentina.

Mercedes-Benz’ former works drivers, mechanics and engineers turned their attention to vehicle repairs in that early post-war period. As the automotive historian Louis Sugahara recalled, a talent for improvisation honed over a number of years had equipped the racing team’s experts more effectively for the job in hand than their counterparts in production. It wasn’t until 1950 that the motor sport department was back in business – on the initiative of Daimler-Benz Chairman Wilhelm Haspel and under the proven leadership of Alfred Neubauer. Neubauer’s first task was to round up some functioning Grand Prix cars from the 1930s. Out of a total of four W 154 models (two of which the company purchased using a new Mercedes-Benz 170 V as bait) and six racing engines, the motor sport engineers built three operational race cars with four engines. The competitiveness of these freshly restored Silver Arrows, which had delivered Mercedes-Benz so many Grand Prix victories more than a decade earlier, was put under the microscope in two races in Argentina in 1951. Hermann Lang, Karl Kling and the local man Juan Manuel Fangio drove impressively in Buenos Aires, Lang and Kling recording second place finishes on February 18 and 24 respectively. However, the performance of the fast but heavy cars was no longer sufficient to secure race wins. Rudolf Caracciola, Mercedes-Benz’ most successful driver before the war, had suggested as much to Alfred Neubauer even before the team left for Argentina, and turned down the offer of a drive in the revived Silver Arrows. Initially, Neubauer also had his sights set on the 1951 Indianapolis 500 race, but pulled the plug on that idea on the back of the lessons learned in Argentina. The same year saw the presentation of the 220 (W 187) and 300 (W 186 II) – the first new passenger car models of the post-war period. The Mercedes-Benz 300 gained widespread familiarity as, among other things, the car of choice for Konrad Adenauer, the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany. However, the “Adenauer”, as the car became popularly known, also provided the nucleus for the brand’s motor sport success in the years that followed. For example, Rudolf Uhlenhaut developed the

The same year saw the presentation of the 220 (W 187) and 300 (W 186 II) – the first new passenger car models of the post-war period. The Mercedes-Benz 300 gained widespread familiarity as, among other things, the car of choice for Konrad Adenauer, the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany. However, the “Adenauer”, as the car became popularly known, also provided the nucleus for the brand’s motor sport success in the years that followed. For example, Rudolf Uhlenhaut developed the

300 SL (W 194) sports car on the basis of the W 186 II series. This model later provided the foundations for the series-produced W 198 Gullwing coupe (1954) and roadster (1957). Uhlenhaut, who had already held the post of Technical Director at the motor sport department before the war, took over as head of Testing in Passenger Car Development in 1949. The first racing success for the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL

The first racing success for the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL

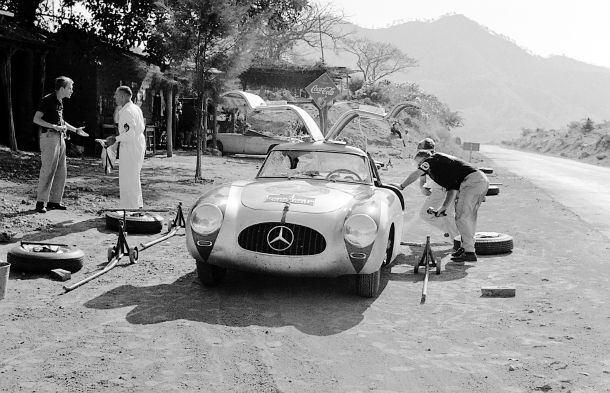

Uhlenhaut designed a tubular frame for the new SL (“Sport Light”) model and added an aluminium body with distinctive gullwing doors. The car owed its door design to the (initially) extremely high entrance edges caused by the space frame, which left no room for conventional, side-hinged doors. This sports car variant of the Mercedes 300 hit the roads in 1952, powered by an engine developing 126 kW. The 300 SL celebrated its racing debut in the Mille Miglia, Karl Kling taking second place and Rudolf Caracciola finishing fourth. For Neubauer, this was a dream come true. “That was the day when my second youth began,” the racing manager later recalled.

Next up was a 1-2-3 (Kling leading home Hermann Lang and Fritz Rieß) in the Bern sports car race on May 8, 1952. However, it was 1-2 victories in endurance races that propelled the return of Mercedes-Benz to motor racing into the global consciousness. At the Le Mans 24-hour race on June 13 and 14, Lang and Rieß took the honours from Theo Helfrich and Helmut Niedermayr. In November, meanwhile, Kling and Hans Klenk crossed the Carrera Panamericana finish line ahead of Lang and Erwin Grupp in the second 300 SL, despite a now legendary collision with a vulture.

While the 300 SL was stacking up the wins, preparations were already underway in Stuttgart for the brand’s return to Grand Prix motor racing. In 1951, and with Daimler-Benz’ Technical Director Fritz Nallinger already expressing his interest in Neubauer’s vision, FIA (Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile) announced fundamental changes to the Formula One specifications for the 1954 season. The regulations for this new blue-riband category of motor racing had actually been drawn up by the FIA back in 1948 and a Formula One drivers’ championship had been held since 1950. Up to 1954, racing cars with maximum displacement of 1.5 litres with supercharger, or

4.5 litres without, were eligible for the series. The new race formula for the 1954 season also allowed for two technical options, but with significantly reduced displacements. Supercharged engines were to be of no more than 750 cubic centimetres, naturally aspirated engines a maximum of 2.5 litres. This amendment presented Mercedes-Benz with an excellent opportunity to return to Grand Prix racing, as the new regulations required all participating brands to enter cars which were either totally new or at least heavily modified.

By the start of 1953 Fritz Könecke, Chairman of the Board at Daimler-Benz AG, had put the finishing touches to an ambitious masterplan designed to carry Mercedes-Benz works drivers to the world championship title in both Formula One and sports car racing. Chief Engineer Hans Scherenberg had the job of coordinating the brand’s efforts, and Technical Director Rudolf Uhlenhaut and racing manager Alfred Neubauer were in charge of turning the brand’s lofty aims into reality. To this end, the motor sport department recruited reinforcements across the board, with 200 employees eventually on the payroll and another 300 experts in other Daimler-Benz departments standing by to offer further assistance. 1953 was dominated by the development of the new Grand Prix car, with the company withdrawing from competitive races for the season to focus on this primary aim.

The return to Grand Prix racing

The new Silver Arrow W 196 R celebrated its premiere in 1954. The new model, which initially lined up with a streamlined body, was powered by a 2496-cc naturally aspirated engine. At the start of the season, this power plant developed peak output of 188 kW and produced a top speed of 260 km/h. Alfred Neubauer had recruited Juan Manuel Fangio to spearhead the brand’s return to Grand Prix motor racing. However, with the season about to get underway the cars were not yet ready for competition and the drivers had to wait until the season’s third race, the French Grand Prix, to sample the Silver Arrows in race action. The fully streamlined W 196 R wasted no time in setting the fastest time in practice for its debut outing on July 4 in Reims, before comfortably exceeding the expectations of public and rivals alike during the race proper. Fangio and Karl Kling recorded a stunning 1-2 victory – a sensational performance with a historical footnote. Mercedes racing cars had also won the French Grand Prix in Reims 40 years to the day earlier, on July 4, 1914. Christian Lautenschlager, Louis Wagner and Otto Salzer filled the top three places in the race.

Following the sports car triumphs in 1952 and the development of the Grand Prix car in 1953, the motor sport department mounted a successful challenge for the world championship title in 1954 with Juan Manuel Fangio the man at the sharp end. The restricted visibility from inside the streamlined Silver Arrow had hindered the team’s progress in the British Grand Prix at Silverstone’s airfield circuit on July 17, with Fangio unable to finish any higher than fourth. However, Uhlenhaut had already commissioned a second, classical monoposto variant of the W 196 R. There were also the benefits of new tires to look forward to, which Continental had developed for Daimler-Benz. At least one Silver Arrow driver finished on the podium in each of the remaining races of 1954, Fangio winning the Grand Prix races in Germany, Switzerland – where Hans Herrmann took third place – and Italy and finishing third in Spain. Fangio clinched the 1954 Formula One World Championship crown with his win in the Grand Prix of Switzerland in Bern-Bremgarten on August 22.

Thinking big for 1955

In 1955, and having provided repeated evidence of their impressive performance over the previous few years, the racing and sports cars now had the opportunity to add the majestic finishing touches to a great racing adventure. Indeed, over the course of the season, it became clear that this would be the Silver Arrows’ last year in competition. Given the importance Mercedes-Benz had placed on the development of new passenger cars in particular, the company could simply not afford to allow the talents of superlative designers such as Rudolf Uhlenhaut to be focused almost exclusively on motor sport. In addition, the benefits gained from experience on the racetrack in the development of cars for volume production had, by 1955, long fallen short of those offered by the first-generation Silver Arrows of the 1930s.

The motor sport department vested its hopes for the 1955 season on an improved Grand Prix car and the 300 SLR (W 196 S) racing sports model. Neubauer had recruited Englishman Stirling Moss as the second star of the team alongside Juan Manuel Fangio. Moss reminded George Monkhouse – a chronicler of Mercedes-Benz racing history mid-way through the 20th century – of his friend Richard Seaman. Seaman, who was killed in an accident at the Belgian Grand Prix in 1939, had been Mercedes-Benz’ first ever British works driver. Fangio and Moss were joined in the brand’s driver line-up for various races during 1955 by a number of other drivers including Peter Collins, Werner Engel, John Fitch, Olivier Gendebien, Hans Herrmann, Karl Kling, Pierre Levegh, André Simon, Piero Taruffi and Wolfgang Graf Berghe von Trips.

The W 196 R had shown one or two weaknesses in the final few races of 1954, prompting the engineers to give the car a thorough overhaul in the close season. “Even after the start of the 1955 season, the cars continued to be modified between races,” observed the historian Louis Sugahara. That applied not only to the engine, but also to the chassis of the cars. In addition to the chassis with long 2350-millimeter wheelbase, 1955 also saw the introduction of a medium chassis (140 millimetres shorter) and the “Monaco” variant, which had a 2150-millimeter wheelbase. In the second half of the season, the racing car also lost 70 kilograms in weight but gained 22 kW in additional output. The W 196 R engine now developed 213 kW at 8400 rpm and maximum speed was bumped up to around 300 km/h. From the outside, the second-generation W 196 R could be recognized by the air scoop fitted on the hood to accommodate the modified intake manifolds.

Argentina calling

The 1955 season began with the Grand Prix of Argentina, a race that developed into hell on earth for the drivers. Temperatures approaching 37 degrees Celsius proved too much for one driver after another, but Fangio held on to win. The race lasted for three hours and theMercedes-Benz man was the only internationally recognized driver to complete the full distance without being replaced by a team-mate for at least part of the way. Only the local sports car driver Roberto Mières could match this feat, bringing his Maserati home in fifth. Stirling Moss, now driving for Mercedes-Benz, fell victim to ill fortune when, recovering by the side of the track from a brief bout of dizziness, he was carried off against his will by the emergency services, loaded into an ambulance and whisked away. Only on his arrival in hospital was he able to make himself understood and return to the circuit. Moss duly took over the car driven at various stages of the race by Hans Herrmann and Karl Kling and shared his fourth place finish with his two team-mates.

Neubauer's report on the Grand Prix of Argentina reads like a commentary: “The race became a torment for drivers and cars alike. They were dropping like flies and the engines also struggled to cope. Gonzales was spent, Farina could make it no further, Castellotti was suffering from heatstroke, Hans Herrmann collapsed exhausted, Harry Schell was cut down by sunstroke, Trintignant staggered into the pits exhausted and Roberto Mières arrived gasping for breath. But with 28 laps gone, Fangio was still in the lead.” And that is where the Argentinean remained on his way to victory in front of some 400,000 ecstatic local fans. Neubauer later called Fangio's victory “one of the greatest performances of his career.”

Fangio followed this up with victory in the Grand Prix of Buenos Aires only 14 days later. Four Silver Arrows lined up at the start for the race on January 30, with the W 196 R powered by a new engine. The motor sport department was using the opportunity offered by an open-formula race to test the three-litre power unit due to be fitted in the new 300 SLR under race conditions. After the rubber coating on the tires used for the first race proved to be too thick, the mechanics made adjustments for race no. 2 to deal more effectively with the hot weather – and Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss promptly completed a 1-2 victory in this high-speed test run. Karl Kling finished fourth.

The unbeatable record: Stirling Moss and the Mille Miglia

The Mercedes 300 SLR finally made its race debut on May 1 in the Mille Miglia thousand-mile race starting and finishing in Brescia, Italy. Already the world's most popular and famous road race, the Mille Miglia celebrated its 28th running in 1955. That year Alfred Neubauer entered four racing sports cars. Although the designation and bodywork of the racing sports car were similar to the 300 SL of 1952, the SLR had a lot more in common technically with the Grand Prix Silver Arrow, a relationship confirmed by its internal designation W 196 S. In addition to the four new cars, the line-up of 520 vehicles for the long-distance race also included several Mercedes-Benz 300 SL cars and even three Mercedes-Benz 180 D diesel saloons. The 1597-kilometer route took the cars from Brescia via Padua, Ferrara and Pescara to Rome, and then via Florence, the Futa and Raticosa passes, Bologna and Piacenza back to Brescia. The race favourite in 1955 was Juan Manuel Fangio, who was bidding to become the first non-Italian since Rudolf Caracciola to win the Brescia thousand-mile race. Caracciola had taken the spoils in 1931 in his Mercedes-Benz SSKL.

The four Mercedes-Benz racing sports cars moved into the top four places on the route out to Rome. However, leading the way wasn’t Fangio, but the young Englishman Stirling Moss and navigator Denis Jenkinson. For Neubauer, though, this position was a bad omen: “There's an old rule, a kind of curse, that hangs over this race: the lead driver in Rome has never won the Mille Miglia. It's not looking good for Moss.” Karl Kling subsequently retired following an accident shortly after leaving the Italian capital, and Hans Herrmann and Hermann Eger were undone by a fault with the tank filler neck. Moss continued to turn the screw over the Apennines and through the Bassa, secured the Gran Premio Nuvolari for the fastest passage between Cremona and Brescia and romped home in a record time for the Mille Miglia, which remains intact to this day. The Mercedes-Benz driver needed only ten hours, seven minutes and 48 seconds to cover the race distance, equating to an average speed of 157.65 km/h.

Moss' victory can be traced back to a number of factors: the skill of the driver, the strategic genius displayed by Alfred Neubauer in the meticulous planning of his team’s fuel supply, the extensive practice runs, Jenkinson's roadbook and the outstanding Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR, which laid down a powerful claim to supremacy in the sports car championship on its debut outing in Italy.

In addition to overall victory, Mercedes-Benz also took the honours with a trio of 300 SL cars in the over 1300-cc GT class, as well as top position in the diesel class in the shape of three Mercedes-Benz 180 D racers.

Mercedes Benz Racing Cars- Clásicos Deportivos Mercedes Benz