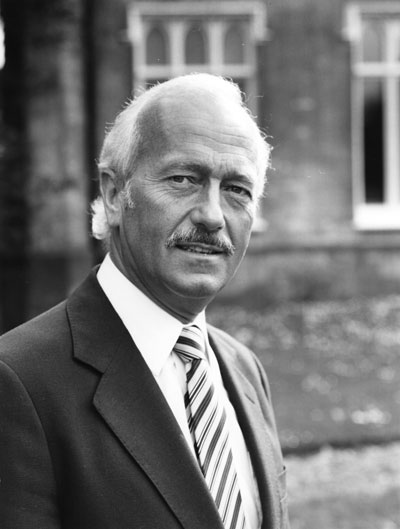

La historia de Lotus en la competición está inextricablemente ligada a la agitada vida del piloto Colin Chapman.

Para la compañía, los títulos de Colin Chapman más los éxitos en las carreras de F1 hablan por sí solas: desde 1958 cuando el equipo Lotus empezó a participar en los Grandes Premios hasta que bajo las persianas en 1994, el equipo había ganado 79 de 491 Grandes Premios, ganando siete campeonatos del Mundo de constructores y seis títulos de pilotos de F1. Lotus también ganó la Indy 500 y tres victorias en su clase, en las 24 horas de Le Mans.

Chapman's record of success in F1 racing speaks for itself: from 1958 when Team Lotus entered Grand Prix racing until 1994 when the shutters finally rolled down, the team won 79 out of 491 Grands Prix, gaining seven F1 World Championships as Constructors and six Drivers' titles. They also won the Indianapolis 500 and a string of class wins in the Le Mans 24-Hours.

Like Enzo was Ferrari and Frank is Williams, Chapman was Lotus. Conceiving, designing and constructing racing cars was not merely a career, it was his very existence. His restless intelligence thrived on competition, demonstrated in win-at-all-costs combativeness. Where he led, others eagerly followed, such was his charisma. He was a swift and mostly accurate judge of character and quickly recognised people who could be useful to him and how he could best elicit their assistance. This was an attribute he'd exploited at an early age when, as leader of Hornsey Air Scouts, he'd motivated his troop to construct and win soap-box derbies. He played the game at corporate level too. In 1964 when Honda sought a partner for its Formula 1 venture, Chapman accepted, but only to bring pressure on Coventry Climax who were vacillating on further development of their own V8 for 1965.

He was a past master at spotting driver talent, bringing numerous aces to the fore; he loved a racer, naturally warming to Clark, Andretti and Peterson. Yet he was a totally ruthless disposer of people when they were no longer useful. On a good day, such as a Team Lotus victory or the Lotus annual ball, he was excellent company. The theatrical hurling of his cap into the air as his winning car crossed the finishing line was genuine exultation. On a bad day it was best to give him a very wide berth.

Known variously by Team personnel as "The Old Man", "Guv'nor," and "Chunky" by less respectful members of the media, Chapman commanded wholehearted loyalty from his workforce. Why else would a bunch of hard-bitten mechanics be prepared to graft all night changing an engine or fixing a crashed car prior to a Grand Prix unless inspired by their boss? Their efforts were genuinely appreciated, even if it didn't always appear so. In the film of the 1973 F1 season, "If you're not winning, you're not trying hard enough" (a Chapman quote), he describes the mechanics as "the salt of the earth."

Innovator and entrepreneur, Chapman could visualise how someone else's idea could be manipulated or expanded to create a masterpiece. The monocoque chassis of the Lotus 25 F1 car is a case in point, sketched on a paper napkin one lunchtime by erstwhile Lotus director John Standen and seized on by Chapman shortly afterwards. Said Lotus Developments' general manager Ron Hickman, "it didn't matter to Colin where the idea had come from, just as long as it was a good one."

Chapman could be hard on his closest lieutenants. When pitching to Player's Geoffrey Kent, where rapport was excellent, for the £345,000 to build the ground-effect Type 78 F1 car, Chapman tore into his engineering boss Tony Rudd for merely asking for the money and not selling the concept to the reeling Player's chief. Rudd was obliged to go back to Nottingham and give the sponsor chapter and verse before Player's stumped up. Chapman was paranoid about leaked information getting into the press. Designer Martin Ogilvie remembered, "If something got out, he would come storming in, saying 'I told you it was a secret! If someone's been blabbing down the pub I'll dock his pay!' But it always ended up being him because he'd been boasting to his mates." Off duty it was another matter. The man who started the bread roll fights at Team Lotus balls had a good aim, and was partial to a bit of shooting. There was a large gun cupboard at Ketteringham Hall, and TL director Tony Rudd told of Chapman putting his head round his office door at twilight, asking "what about the ducks, then?"

Already his methodology was clear. From the earliest days he surrounded himself with a small, close-knit coterie of experts and talented enthusiasts prepared to graft all hours because they believed in the objective just as much as the man. His charisma attracted such types and they basked in the glow of what the race team and associated car company achieved. Although surrounded by clever designers and technicians, at the end of the day he was Lotus chief engineer. With a degree in structural engineering from UCL, Chapman learned to fly during National Service in the RAF and served an apprenticeship at De Havilland, where he became familiar with state-of-the-art aeronautical technology. His first steps in car design embraced aircraft principals. Joined by a trio of De Havilland design engineers, Mike Costin, Peter Ross and Gilbert "Mac" Macintosh, Chapman and his associate Michael Allen espoused 750 Motor Club ideals and came up with the Lotus Mk 6, forerunner of the Seven, the "four-wheeled motorcycle", a concept so good it's still in production today at Caterham Cars, not to mention sundry other replicants.

By the late-1950s Chapman was operating a quasi-philanthropic DIY race car service, in which he provided the customer with the makings of the car, they built and raced it, and Chapman creamed off the start money, bonuses and winnings as well as retaining ownership of the car. Up-and-coming drivers like Graham Hill and Trevor Taylor could handle state-of-the-art machinery like the Eleven and Type 18 which they knew inside out as they'd constructed the cars themselves. This was an extension of the self-build philosophy that prevailed in the impecunious post-war years, and Chapman founded the Lotus road car business producing Mk 6s and Sevens in component form on the back of the purchase tax-free rules governing kit car sales.

Chapman flew himself wherever possible, and his aviator's vision relocated the factory from Cheshunt to Hethel and its ready-made airfield in 1966. The entrance to Reception faces the test track because that was the direction he envisaged the majority of visitors arriving from, having come by plane. No mean racing driver, he won numerous races in his own sports-racing cars in the early 1950s and he was hired by the Vanwall F1 team as third driver alongside Mike Hawthorn and Harry Schell for the French GP at Reims in 1956; a practice crash put paid to that, and his insurance company forbade him to race thereafter. It was a pivotal moment: no longer the racer and race-car builder, he would henceforth be a constructor. Nevertheless, he was still to be seen misbehaving in an Escort celebrity race in the late-1970s. Others were less convinced of his prowess behind the wheel. Chief mechanic Bob Dance said, "in a car with him driving I'd probably feel quite uncomfortable, whereas in a plane with him at the controls I'd be absolutely fine."

The preoccupation with aerodynamics became apparent as early as 1954 with the Mk 8, its all-enveloping curvaceous body the work of Frank Costin, still employed at De Havilland aircraft. That was succeeded by the Mk 9, with which Chapman made his first entry at Le Mans, and the Mk 10, the design tightened up with the sublime Eleven (its designation spelled out like the Seven, rather than a numeral) which was made from 1956 to '58 and yielded class wins at Le Mans three years running. Asked what it was like in the wet, Chapman responded, "a bit choppy round the ankles."

Chapman acted as a consultant on the Vanwall F1 car, a sleek - if bulky - Costin design, and his F1/F2 Lotus 16 of 1958 reprised the Vanwall in a much neater form. Coincidentally, the Elite sportscar appeared in December 1958, the Kirwan-Taylor design as elegant as anything to emerge from an Italian styling house. Not just a pretty face, it won its class at Le Mans six years running, and took Lotus into the mainstream car industry. Chapman's second mid-engined Formula 1 car, the Type 21 from 1961, stood the form-book on its head, with relatively tiny frontal area, inboard front suspension, and the driver recumbent. Then came the Type 25, one of the most successful Lotus racing cars, evolving into the Type 33 and driven by Jim Clark to two World crowns in '63 and '65. Its ground-breaking aluminium monocoque tub set the agenda for a generation of F1 cars, and it emerged at a time when the company was involved across the board in saloon car racing with the Cortina, sports racing with the Type 23, Formulae 2 and 3, and Indianapolis. Chapman virtually founded the British racing car industry and, as his then right-hand-man Mike Costin commented, "everything we made was related to whatever Colin wanted to push through." That extended to gearboxes with the Lotus built five-speed "queerbox" transaxle of the late '50s and early '60s, and engines with the Ford-based Lotus twin-cam of the '60s and the Vauxhall-derived 907 twin-cam of the '70s and '80s. By 1983 there were even microlight aeroplane engines on the testbed. Where Chapman led, the rest followed. In 1967, the Type 49 was first to run the 3.0-litre Cosworth DFV engine, the power-unit bolted directly to the rear chassis bulkhead and acting as a stressed chassis member, where previously (apart from the Type 43) it had been mounted within spaceframe or monohull. A couple of seasons on, the Lotus engine configuration was ubiquitous across the grid, barring V12 adherents Ferrari and BRM.

Lotus didn't just pioneer technical solutions; for 1968 Chapman made a deal with Imperial Tobacco to bring big-time trade sponsorship to motor sport, an area that had previously been the province of US teams. By presenting his cars in spectacular Gold Leaf livery, at a stroke he changed the look of the sport forever, opening the floodgates to a raft of commercial backers who had little or nothing to do with the automotive industry.

Shortly afterwards, Chapman was first European constructor to experiment with lofty adjustable rear wings mounted on the Type 49's rear uprights. The driver could tilt the aerofoil to achieve more downforce as he approached the bend and feather it on exit for maximum straightline speed. Chapman wasn't afraid to take risks, although it was Hill and Rindt rather than he who clambered from the wrecks at Barcelona when too-tall wing supports failed.

From the early days in Formula 1, Lotus had a reputation for fragility, partly due to Chapman's fixation with lightness but not always justified; inevitably, drivers had big accidents if they broke. Chapman was not immune to the pain of loss when a driver got killed. His bond with Clark was dashed on 7th April 1968 at Hockenheim, and he was devastated by the death of his friend and protege. Team manager Jim Endruweit believed he was ready to throw in the towel, a decision compounded when Mike Spence was killed less than two months later at Indianapolis. Graham Hill's ebullience and stoicism held it all together, emerging from months of bleakness with the World Championship.

Chapman's obsession with fine-tuning airflow was a recurring theme. The succession of sports-racing cars from the mid-'50s were as aerodynamic as anything else on the circuit, and in 1958 Frank Costin evolved an inflatable tonneau cover (like a li-lo) for the Eleven that passed from the top of the windscreen to the rear bodywork, virtually enclosing the cockpit. It improved aerodynamics and rigidity at high-speed Le Mans, and just squeezed within the regulations. That was another Chapman trait: to adapt the rules to his own ends, gaining what he described as "the unfair advantage" over the opposition. There were other enhancements, like the air-jet screen on the Type 25 and subsequent '60s single-seaters, and there were major shifts in configuration such as the "wedge", first manifest in the gas-turbine Type 56 Indianapolis car from 1968. The following year even the most junior Formula Ford racer could drive a wedge-shaped Type 61. Although the four-wheel drive Type 63 proved a dead duck in F1, when the side-radiator Type 72 wedge appeared in 1970 the rest weren't far behind. People waited to see what he would do, then copied it. It even happened in road cars; what's the Mazda MX5 but a copy of the Lotus Elan? Still, as they say, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Chapman himself wasn't above that. Enzo Ferrari produced and sold road cars to enable him to go racing, and Chapman held the same philosophy. Moreover, this ambition spurred him on to a great extent, resulting in the upmarket shift from Elan sportscar to wedge-shaped Elite Grand Tourer in 1974. With the launch of the Giugiaro-styled Esprit in 1975 and the turbocharged version in 1980, Lotus was knocking on the door of the exalted supercar brigade.

The next march that Chapman stole on the F1 firmament was "ground-effect". To generate maximum downforce to gain superior traction and roadholding, he visualised a car configured like an inverted wing. By harnessing air flow under the chassis by means of venturi in the sidepods and trapping it underneath by means of side skirts the whole vehicle was sucked down onto the track. The faster it went the more downforce was generated. Here was something for nothing! Pioneered in the Type 77, the ground-effect concept came to fruition with the Type 78 and matured with the Type 79, which Mario Andretti and Ronnie Peterson used to overwhelming effect in 1978. Predictably, the opposition set about copying the Lotus, Williams making the best job of it with the FW07 and enabling Alan Jones to scoop the title in 1980. As Team Lotus aerodynamicist Peter Wright observed, "after ground-effect there was no going back." It was like a loss of innocence; we now knew too much, and all subsequent race car design has been obliged to take ground-effect into account, even when skirts were banned.

It didn't always go Chapman's way. Doubtless the authorities at Le Mans had been itching to get back at him for trouncing the homespun Panhards in the Indices of Performance and Thermal efficiency, and in 1962 they delighted in excluding the Type 23 for having four studs securing the front wheels and six on the back. Ludicrously, they claimed it wasn't safe. Outraged at such blinkered petty-mindedness, Chapman never went back. Fast-forward twenty years to the ground-effect era, and he was seeking a way to alleviate the pounding ride that drivers were subjected to, aware that a comfortable driver can operate at his peak for longer as well as keep his feet on the pedals. (This was the man who, in the dim and distant past, had sliced off the curved base of the driver's seat to lower the centre of gravity in the Type 22 Formula Junior car under his "theory of the compressibility of bums" so the driver effectively sat on the floorpan!) Downforce requires stiff, almost non-existent suspension, while ride comfort requires the opposite. Accordingly he came up with the twin-chassis car, the Type 88, combining the best of both worlds. The outer unit was a ladder chassis that carried the ultra firm suspension that supported the ground-effect loads, and within that was the inner chassis with conventional wishbone type suspension that carried the powertrain and cockpit, a principal related to modern-day truck cabs. At speed, the side-pods of the outer chassis were sucked to the track surface as ground-effect took hold. As far as the more litigious constructors and FISA rule makers were concerned, he'd gone too far, and the Lotus was hounded out of play. Chapman didn't let it drop; he fought for the right to innovate, and although technical experts couldn't fault the concept, in a succession of court cases the political rule makers' argument held sway. As he'd done at Le Mans two decades earlier, Chapman turned his back on the damning authorities and was seriously preparing to get stuck into microlight planes when he died, aged just 54. He wasn't about to abandon racing, however, since he'd paved the way for Lotus to run the turbocharged Renault F1 engines in 1983, and computer-controlled active-ride suspension was on the stocks. He'd brokered a tie-up with Toyota to use its components in Lotus road cars too.